What's Going Wrong with ULCCs in the US?

Cyclical bump or secular challenges? A little bit of both, but we think problems for the US ULCCs are here to stay.

Once the growth-powered darlings of Wall Street, ultra low-cost carriers (ULCCs) in the US have come into tough times. The two largest, Frontier Group (ULCC-US) and Spirit Airlines (SAVE-US), posted 3Q23 losses even as the “legacy carriers” recorded healthy profits. Frontier and Spirit lost money in 1Q23 as well, and consensus sees continued losses in 4Q23.

Share price performance has been dismal too, with Frontier shares down ~63% since the beginning of 2022. Spirit shares have fallen by ~22% over the same period, although its share price gets support from JetBlue’s pending bid. Southwest and Allegiant have also lagged the network carriers. Meanwhile, Delta and United shares are around flat over the same period.

Why have ULCCs in the US (particularly Frontier and Allegiant as well as Spirit before market-implied odds of its takeover increased) been struggling so much? United (who provided a very clear explanation on their recent earnings call) believes the primary cause is “cost convergence” between legacy carriers and ULCCs. We agree that cost convergence likely plays a role (and the effects will likely continue to grow), but it may not be the most important factor.

Instead, we believe the ULCC business model in the US may be fundamentally challenged. Legacy carriers have perfected the art of yield management to achieve profit maximizing customer segmentation. As part of this segmentation, the US airline industry is going through a period of enduring “de-commodification” that favors legacy carriers with differentiated products. Loyalty programs and scale are more closely tying legacy carriers to the daily lives of flyers, helping increase retention and build new revenue streams.

Regarding permanence, United expects the cost convergence headwind for ULCCs to remain in play for the foreseeable future. We agree, for some of the causes. But many of the causes they cite, as we will explain below, could ultimately prove transient over the medium term, making cost convergence a temporary phenomenon.

Instead, we believe the revenue side will remain a key, favorable differentiator for US network airlines. The success of their customer segmentation and retention initiatives could create a permanent advantage over US ULCCs.

The Real Story is on the Revenue Side

Does lowest cost always “win the race” in the airline industry? Until recently, intensive cost management has been the route to success . LCCs and ULCCs were the growth darlings of investors, who viewed them as the future of the industry and overall market share winners. But the struggles of ULCCs over the past few quarters have called this narrative into questions.

We can look to the numbers to try to discern why ULCCs have struggled so much recently vs. the legacy carriers. These numbers tell a bit of a different story than United is pitching, but one that nonetheless is good for network carriers. In our opinion, the spotlight should be on the revenue side of the income statement (as opposed to the cost side).

In 3Q23, the differences in TRASM and seat yields between the highest and lowest US carriers were 10.77 and 13.98 cents, respectively. The differences in highest and lowest CASM-Ex Fuel and CASM were smaller, at 6.36 and 7.74 cents, respectively. We can already start to draw two conclusions: 1) Cost differentiation in 3Q23 was smaller than revenue differentiation among US airlines (perhaps giving some credence to United’s theory of cost convergence); and 2) As a result, revenue, not cost, was the more important differentiating factor for US airlines in 3Q23.

But to evaluate cost convergence, we need to examine change over time. Looking back to 2019, we can see that the spread between highest and lowest TRASM has increased significantly, while the CASM spread actually increased modestly. In 2019, the TRASM spread between highest and lowest US airline was 8.15 cents. This figure increase +32% to 10.77 cents in 3Q23. On the other hand, the CASM spread actually increased (instead of declining, as cost convergence would imply) by +7% to 7.74 cents last quarter vs. 7.26 cents in 2019. The spread between highest and lowest margin per available seat (“MASM”) increased from 1.33 cents in 2019 to 4.01 cents in 3Q23. Widening revenue per seat differentials appear to be the key driver of diverging margin per seat figures.

It’s worth pointing out one caveat to this conclusion that is embedded in the numbers but not directly observable. As we will discuss below, we believe “premiumization” (as part of improved customer segmentation) is behind higher TRASM at the network carriers, and premium products typically increase CASM. This increase stems from both higher service costs per premium seat and a reduction in total seats due to the replacement of economy seats with fewer front-of-cabin seats (hence fewer available seat miles to absorb fixed trip costs). Of course, higher unit costs are presumably offset by higher unit revenues.

It is possible that, without some degree of cost convergence, the CASM spread would have increased more than it actually did from 2019 to 3Q23 due to premiumization over the period. In other words, cost convergence in some areas (e.g., pilots) in large part offset the effect on network carrier unit costs of premiumization. It’s difficult to observe this phenomena because it involves a counterfactual, but with this in mind, we’ll discuss some areas where costs are converging in more detail below.

Customer Segmentation

Now that we’ve established TRASM divergence and not CASM convergence is the major driver of margin divergence among US airlines, let’s consider why TRASM is diverging. We believe that US legacy carriers have finally figured out how to optimally segment customers, which allows them to revenue maximize.

In the “old days” (essentially pre-1980) there was first class and economy class. The difference (including price) between first and economy classes was quite large. Hence, there was a significant product gap. Customers with a willingness to pay above the price of an economy seat but below the price of an expensive first class seat settled for economy and the airline missed out of the extra revenue (equal to willingness to pay less economy price).

By the 1970s, airlines began experimenting with business class as an intermediate product between economy and first. Initially, business class was just a slightly nicer version of economy (akin to today’s economy plus or comfort plus product) for full-fare economy customers. In 1979, Qantas introduced what many consider to be the first “true” business class product. It cost about 15% more than economy and had larger seats and better service.

Over time, business class became more and more like first class until many airlines actually dropped first class service altogether. In other words, business class didn’t really solve the price segmentation problem. The gap between business class and economy started out too small and eventually became too large, leaving revenue on the table.

In 1999, United introduced Economy Plus, an economy-style product with slightly more legroom that sold at a small premium to economy class tickets (like the original business class product did). Delta followed with Comfort Plus (stylized Comfort+) in 2011, while American added Main Cabin Extra in 2012.

In 2012, Delta pioneered Basic Economy with a limited rollout, followed by a more extensive launch in 2014. United and American followed suit in 2017. Basic Economy is essentially a partially unbundled version of economy designed to compete with the cheaper unbundled products offered by LCCs/ULCCs. It uses the same seats as regular economy, reducing operational complexity. For example, the Delta Basic Economy fare does not allow advance seat selection; boards last; offers no frequent flyer miles; is not eligible for upgrades; does not permit changes; and incurs a cancellation charge. Unlike with earlier low-cost products offered by legacy carriers (e.g., United Ted and Delta Song), the basic economy product is offered on the same aircraft as higher fare products.

Finally, American launched its Premium Economy product in 2016. Delta started offering Premium Select in 2017 and has been gradually rolling out this class of service on its aircraft since. Only recently has it reached widespread implementation. United followed with Premium Plus in 2018. Premium Select and similar products offer larger, more comfortable seats with enhanced cabin service, similar to business class before it went lie-flat. ,

Today, an international or transcontinental flight operated by a US network carrier might have five classes of service (Basic Economy, Economy, Economy Plus, Premium Economy, and a first class-style branded product), while a mainline domestic flight might offer four classes (Basic Economy, Economy, Economy Plus, and First Class). For example, a round-trip ticket on a Delta flight to Paris from JFK in July 2024 currently costs $997 for Basic Economy; $1,177 for Main Cabin (Economy); $1,861 for Comfort+ (Economy Plus); $2,584 for Premium Select; and $4,381 for Delta One (branded first class).

The airlines now cater to four or five price points, meaning they can more closely target each individual customer’s specific willingness to pay, resulting in improved revenue maximization. And they are doing this targeting using one plane instead of the operationally complex LCC airlines-within-airlines used in the past.

The final piece of the puzzle has been widespread adoption of premium travel products by leisure travelers in the wake of the pandemic. Previously the domain of business travels, first class and premium select are seeing consistent uptake by leisure travelers with cash to spare. This is a critical pillar of the strategy’s success, along with the presence, in the first place, of multiple classes. Any softening in premium leisure demand could blow back on the network carriers, particularly as they expand front-of-cabin space at the expense of economy.

Loyalty Programs

The network carriers’ loyalty programs are important contributors to their overall profitability and a key differentiator vs. ULCCs. While ULCCs in the US also have loyalty programs, they are much smaller and likely less significant to the airlines’ overall economics.

Loyalty program disclosure can be patchy and inconsistent, although it has improved over the past few years. In 2022, Delta received cash remuneration (not GAAP revenue, but a good indicator of economic significance) from its partners for SkyMiles of ~$5.7b or ~2.44 cents per ASM. Similarly, American Airlines’ ~$4.5b of remuneration in 2022 for AAdvantage Miles comes out to ~1.73 cents per ASM. In comparison, Spirit’s $81m of loyalty remuneration was only ~0.17 cents per ASM.

The size of the network carriers; their often dominant hub positions; their partnerships with large, brand name card issuers; and of course the time they’ve been around all contribute to their strong loyalty programs. And these loyalty programs in turn are important contributors to profitability and help with customer retention. We’re seeing airline loyalty programs reach further and further into “real life.” Delta recently partnered with Starbucks to offer 1 miles per $1 spent.

It’s hard to see US ULCCs replicating the size and depth of the loyalty programs of the network carriers, at least in the near to medium term. And that hands the network carriers a structural advantage for the time being.

Cost Side: Universal Inflation Should Hurt ULCCs More

Although the revenue side of the equation seems to best explain margin divergence between the network carriers and the ULCCs, it’s still worth examining the cost side. As mentioned above, it’s possible cost convergence has helped reduce the widening of the industry’s cost spread. And it’s also possible the forces of cost convergence disproportionately impact ULCCs in the near future.

We do think that the industry is seeing universal cost inflation that affects both legacy carriers and ULCCs. Universal cost inflation affects all carriers, and while it doesn’t necessarily outright narrow cost spreads (i.e., cause cost convergence), it does inflate ULCC unit costs by larger percentage rates than legacy carrier unit costs. This dynamic, in turn, forces ULCCs to raise ticket prices by larger percentage rates or face margin degradation. Because ULCC customers are more price sensitive than legacy carrier customers (meaning demand elasticity is higher), ULCCs have difficulty raising prices to absorb higher cost levels without denting demand.

Fuel Costs

Universal cost inflation in the past has generally been caused by higher fuel prices, which hurt ULCCs more than legacy carriers (all else equal) via the above described event chain. In addition, a larger proportion of ULCC costs are fuel-related, meaning they are affected more significantly by higher fuel prices. For example, in 2022, fuel costs made up 34% of Frontier’s total operating expenses but only 24% of Delta’s costs. While jet fuel prices have moderated recently, they remain The above pre-pandemic levels and could face an upside shock if geopolitical events affect oil supply.

ATC Problems

The shortage of air traffic controllers, particularly when combined with poor weather, is slowing air traffic across the US and causing both delays and cancellations. More frequent irregular operations mean lower effective utilization rates (both from day-of IROPS and preemptive schedule changes to avoid future problems). ULCCs rely on higher rates of aircraft utilization than legacy carriers to reduce their unit costs, but this strategy becomes more challenging to implement if ATC is causing delays. All airlines in a given area are affected by ATC issues, but as with fuel, the relative impact on low cost airlines can be more significant.

Pilot Costs

The shortage of pilots, particularly in the US, is making hiring and retention more difficult while also pushing labor costs higher. Regulatory changes following the Colgan Air disaster in 2009 require both captains and first officers to hold Air Transport Pilot (ATP) certificates. This change increased the minimum flight time requirements for first officers from 250 to 1,500 hours. We are not here to debate the merits of this change, but it has made becoming a commercial airline pilot more costly and time consuming.

Layoffs and furloughs during the pandemic as well as an aging pilot workforce have all contributed to pilot shortages, resulting in meaningful pilot wage inflation. Delta signed a new contract with its pilots in March 2023 to increase pay by 34% over four years. American Airlines followed in August 2023 with 46% increases in pilot pay, while United followed in September 2023 with raises for pilots of up to 40% over four years.

We are seeing nothing short of a piece-wise reset in pilot pay, and the ULCCs are not immune. Spirit signed a deal with its pilots to raise pay by more than 30% over the two year duration of the contract. But higher pilot compensation has yet to hit Frontier and Allegiant. Frontier’s labor agreement with its pilots will not become amendable until January 2024, while Allegiant has been in a multi-year dispute with its pilots over a new contract. Both airlines could see major cost inflation in the near future, as well as pilot defections and difficulty hiring, that could be hard for them to digest given their customer bases.

The ULCC model in Europe has less trouble (albeit still some) with pilot labor costs. First officers in Europe can start flying in revenue service with as little as 200 hours of flight experience, reducing pilot supply challenges. This is, perhaps, a notably important structural difference between the US and European markets that make the ULCC model more sustainable in Europe.

The average annual salary (as of mid-2022, so current figures are higher and rising) of US ATP pilots is about $225k, according to the BLS. European figures are harder to come by, but pilot pay seems to average roughly €100-€200k a year. There are a variety of figures floating out there, but a Ryanair first officer is said to make about £63k/year while a captain is said to make about £123k/year. An easyJet first officer might make £60-£100k/year while a captain makes about £150k after 10 years of service.

The general point is that pilot compensation in Europe is lower than in the US, in large part due to different training requirements. This important difference (among others) might start to explain why the ULCC model in Europe has succeeded in taking almost 50% intra-continental market share vs. only about 13% in the US (in 2022) or 35% if you include LCC Southwest.

ULCC-Specific Challenges

There are a number of factors specific to ULCCs (as opposed to network carriers) that are affecting their margins. Five major ones stand out: 1) More immature, less profitable routes due to faster growth; and 2) Challenges filling upgauged aircraft; 3) Low-end consumer weakness; 4) Saturation of major leisure markets; and 5) Relative strength in international markets, to which ULCCs are under-indexed. Note that these ULCC-specific challenges may be more transient, to vary degrees, than the structural issues discussed above.

Rapid Growth & Immature Routes

The ULCCs, most specifically Frontier, have been growing aggressively in the US. Frontier increased available seat miles (ASMs) by +20.6% YoY in 3Q23, more than any other US airline. While Delta and United posted strong ASM growth, this was largely propelled by international operations. They only grew domestic ASMs by +11% YoY during the quarter, while American only grew total ASMs by +6.9% YoY. Sun Country and Spirit both posted strong, largely domestic (and near-in international) ASM growth of +15.1% and +13.5% YoY, respectively.

About ~14% of Frontier’s ASMs are in markets less than a year old, although this is less than the ~19% in early 2022. Growth means new, immature routes with lower profitability than established ones. It can also mean depressed load factors (it takes time to generate demand on a new route), particularly if the growth is too much for the market to bear. Indeed, fast growing Frontier posted the lowest load factor of any major US airline in 3Q23 at 80.0%, with Spirit third from the bottom at 81.4%.

Allegiant is a great counter example of what growth discipline looks like. It was the only profitable US ULCC in 3Q23, but it actually slightly shrank ASMs YoY. Careful capacity discipline meant Allegiant achieved a load factor of 87.5%, tied for first place among US airlines in 3Q23.

Upgauging Limits

ULCCs in the US and Europe are pursuing an upgauging strategy to reduce unit costs, but there may be limits to this approach. Spirit is adding A321neos and retiring A319s. Similarly, Frontier’s A321neo order book is more than 2x the size of its A320 order despite its current fleet being weighted towards A320s. Larger aircraft are harder to fill and can therefore have difficulty profitably serving smaller markets. There may be limits to the number of markets that can be served by A321s vs. A319s.

Unlike the other ULCCs, Allegiant has taken a different approach. The airline serves small and medium-sized cities with more manageably sized A320s and A319s, and its order book includes the small and mid-sized 737 MAX 7 and 8-200 variants. Not surprisingly, Allegiant has fared better in the current environment, at least for now.

Low-End Consumer Weakness

From a macro perspective, it’s worth noting that there have been some signs of weakness among consumers, particularly on the lower end. ULCCs like Frontier and Spirit are more exposed to these customers.

Although lower earners have seen higher rates of income growth, inflation has also increased living costs. Consumer confidence has slumped (although it ticked higher in November 2023), the price of gas has been elevated (although it has been falling recently), student loan payments resumed, and pandemic-era stimulus has become a distant memory. Retail and consumer product companies are reporting that consumers are trading down to save money. It seems like inflation plus a combination of fiscal and monetary tightening has been negatively affecting the consumer, particularly the kind of price-sensitive lower earners drawn to ULCCs.

The macroeconomy appears headed for a “soft landing” and inflation is easing, suggesting that ULCCs might get a reprieve on the demand side at some point in the near future. However, spending decisions are often driven by consumer perceptions, which tend to lag changes in the real economy. Hence, it might be a while longer before ULCCs benefit from a stabilizing economic environment.

Major Leisure Markets Are Becoming Saturated

ULCCs and Southwest, alongside legacy carriers, have been dumping new seat capacity into thriving leisure markets such as Florida, Las Vegas, and Cancun. These destinations had seemed like endless wells of demand, but they now appear to be reaching the point of saturation.

Passenger traffic at Cancun International Airport (CUN) in Mexico has grown from 12.4m in 2010 to an astounding 30.3m in 2022, an impressive 7.7% CAGR over 12 years. Traffic rose by +36% YoY in 2022 to 30.3m on the back of post-pandemic “revenge travel,” coming in 19% above the pre-pandemic level in 2019. As of October 2023, trailing 12-month arrivals totaled 32.6m, a +10% YoY increase.

At a certain point, everyone who wants to visit Cancun will already be visiting it, at least in the near term. And indeed, that is what we are seeing in the traffic figures. The +20-30% YoY growth of January and February 2023 as well as the +5-10% YoY growth of March through July 2023 slowed to +0-2% YoY growth starting in August. Cancun, famed for its enormous hotel footprint and seemingly endless inbound airlift, appears to be getting saturated. That means ULCCs may not be able to just place new aircraft in this heretofore “no-brainer” market without depressing load factors and yields.

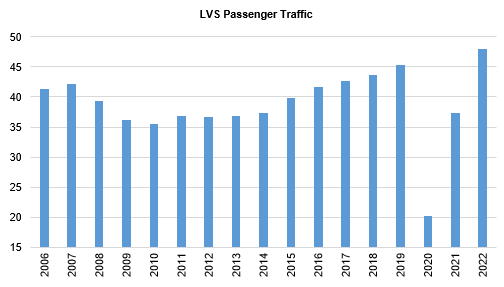

At notable domestic leisure destinations like Las Vegas (LAS) and Orlando (MCO), passenger counts have reached new highs. In 2022, Las Vegas passenger traffic was +29% YoY, while MCO traffic was +17% YoY. As of August 2023, trailing 12-month traffic growth was +10.8% YoY and +9.7% YoY, respectively. Traffic in Las Vegas and Orlando in 2023 was 6.1% and 3.4%, respectively, above pre-pandemic highs in 2019.

But the most recent trailing 12-month growth figures start to tell a story. Growth is slowing vs. 2022 levels as new demand highs are tested. Like Cancun, Las Vegas and Orlando are not endless pools of demand. The ULCCs appear to be hitting a wall, at least for now.

And it is the ULCCs that have been driving growth in many of these major leisure markets. At MCO, ~85%+ of traffic growth from 2019 to 2022 was from Spirit and Frontier. The picture in Las Vegas is similar. American and Delta have seen essentially flat traffic at LAS from 2019 to 2022. Most growth was driven by Frontier, Spirit, and Southwest, in that order.

Relative Strength of International

Finally, international has been particularly strong for US network carriers over the past 12-18 months as countries drop COVID restrictions, China reopens, and people resume international travel. Because ULCCs have less exposure to international than network carriers, they have benefited less from this rebound.

For example, Delta, United, and American saw domestic network revenue change by +6%, +9%, and -2% YoY, respectively, in 3Q23. On the other hand, transatlantic revenue increased by +34%, +15%, and +8% YoY respectively, while transpacific revenue rose by +65%, +15%, and +129% YoY, respectively.

Growth in key international markets not only exceeded domestic growth, but was significantly higher than overall growth at ULCCs/LCCs like Frontier, Spirit, and Southwest. Southwest saw revenue rise by +5% YoY in 3Q23, while Frontier and Spirit experienced revenue declines of -3% and -6% YoY respectively.

As noted above, US ULCCs and LCCs have less exposure to international markets than US network carriers, meaning they benefit less from their rebound. The US ULCCs/LCCs serve the Caribbean and Central America to varying extents, but this can’t make up for the lack of true international networks. Plus, some of the top leisure destinations in these regions are the ones that are becoming saturated. JetBlue expanding into Europe and Allegiant looking to work more closely with Mexican carrier Viva Aerobus are likely ways to tap into strong international demand. But it takes time for airlines to build out international businesses large enough to move the needle.

Important Disclaimers & Disclosures

This report is produced by Jetway Intel LLC (“We” or “Us”), an information services company that publishes airline and aerospace & defense business and financial news and analysis. This report is not an offer to buy or sell securities and is not investment advice. It is for informational purposes only.

This report is presented on an “as is” basis without any representations or warranties of any kind, whether express or implied, including about the accuracy or correctness of information contained herein. We disclaim any responsibility for errors or omissions. We have no responsibility to update or correct information in this report.

By accessing, reading, or subscribing to this report, you agree to hold Us harmless from all liability and claims of damages to the fullest extent permitted by law. Conduct your own due diligence before making decisions of any kind, including investment decisions.

We and our Affiliates (including but not limited to our members, owners, managers, officers, employees, consultants, agents, and representatives) may own securities of and/or derivatives related to companies mentioned in this report or other companies in similar industries.

We and our Affiliates are not responsible for disclosing our security and derivative holdings or changes thereto. We may trade in securities and/or derivatives of companies mentioned in this report or other companies in similar industries at any time and without disclosing such trades (either prior or subsequent thereto).

Please read our full Terms of Use and Privacy Policy.

© 2023 Jetway Intel LLC. All rights reserved.